I always wanted to be somebody. If I made it, it’s half because I was game enough to take a lot of punishment along the way and half because there were a lot of people who cared enough to help me. I’m Althea Gibson, the tennis champion.

— Althea Gibson

Introduction

This quote by Althea Gibson encapsulates both her personal resilience and the communal support that sustained her through a groundbreaking athletic career. As a pioneering female African American athlete, Gibson broke through entrenched racial and gender barriers in both tennis and golf, making history as the first African American to win a Grand Slam tennis title. Her achievements signified not only athletic excellence but also a challenge to the systemic racism that defined the mid-20th century American sports landscape.

Early Life and Education

Althea Neale Gibson was born on August 25, 1927, in Silver, South Carolina, to sharecroppers Daniel and Annie Bell Gibson. In 1930, her family moved to Harlem, New York, during the Great Depression, seeking economic stability. It was there that Gibson discovered her athletic talent, first excelling in paddle [table] tennis. By age 12, she had won the New York City women’s paddle tennis championship, attracting the attention of local tennis mentors who facilitated her entry into organized tennis.

Gibson attended high school in New York City and later matriculated at Florida A&M University (FAMU), a historically Black college. She graduated in 1953 with a degree in physical education. During her time at FAMU, Gibson dominated the American Tennis Association (ATA) circuit, which served as the primary competitive venue for Black tennis players during the era of systemic segregation. [1]

Tennis Career

Collegiate success and major titles came to Ms. Gibson: While at Florida A&M University (FAMU), Gibson continued her dominance in the American Tennis Association (ATA), laying the groundwork for her historic entry into previously segregated international tournaments. Her transition to mainstream tennis culminated in a series of unprecedented victories:

In 1956, she became the first African American to win a Grand Slam tournament, taking the French Open title.

In both 1957 and 1958, she won Wimbledon and the U.S. Nationals (now the U.S. Open).

Over the course of her career, Gibson won 11 Grand Slam titles: five in singles, five in doubles, and one in mixed doubles.

These accomplishments redefined the possibilities for Black athletes in traditionally white sports and served as a catalyst for broader integration within professional athletics (Yven & Dyer, 2021).

Personal Life and Public Identity

In 1965, Gibson married William Darben; they divorced in 1975. She later married Sydney Llewellyn, her former tennis coach, in 1983, but this marriage also ended in divorce by 1988. Gibson did not have children.

Despite limited public documentation of interactions with law enforcement, Gibson’s life remained focused on athletic, social, and civil rights contributions. She did not face major controversies or legal disputes, distinguishing her public persona as one centered on dignity, perseverance, and advocacy.

Advocacy and Civil Rights

As a Black woman competing in overwhelmingly white and elite spaces, Gibson’s success was inherently political. She confronted overt racism and exclusion, and her victories became symbolic wins for the broader civil rights struggle. Scholars have highlighted her as a figure whose success disrupted prevailing narratives about race, gender, and American meritocracy (Brown, 2021; Smith & Hattery, 2020).

Although Gibson did not engage in frontline protest politics, her presence in tennis and golf was itself a profound act of resistance. She frequently spoke about racial inequality in sports and used her platform to encourage greater inclusion and equity.

CONCLUSION: Later Years and Continuing Legacy

After retiring from tennis, Gibson became the first African American woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) in the 1960s.

Althea Gibson’s professional golf career was groundbreaking, though less celebrated than her accomplishments in tennis. Gibson began pursuing professional golf after retiring from tennis in the late 1950s. She had long been interested in golf but faced even greater racial barriers in this sport, which at the time was deeply segregated. She officially joined the LPGA Tour in 1964, at the age of 37.

Her debut marked a historic moment, as she became the first Black woman to compete on the tour. Gibson faced pervasive racism in golf. She was often denied access to clubhouses, forced to change clothes in her car, and was sometimes excluded from tournaments held at segregated golf courses.

Though she did not win any LPGA tournaments, Gibson competed in 171 events and achieved several top-10 finishes. And, while her LPGA career was not as decorated as her career in tennis, her mere presence on the tour was a major step forward for racial integration in golf. After making history as the first African American to win a Grand Slam tennis title, Gibson broke another racial barrier by becoming the first African American woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour in 1964.

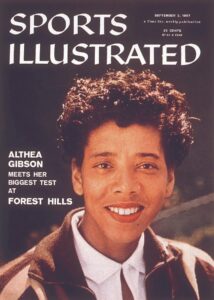

Additionally, she was the first black woman honored to be featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

She paved the way for future generations of Black female golfers, including Renee Powell and later players like Cheyenne Woods.

However, systemic racism and financial barriers limited her success in professional golf, mirroring the struggles she had already faced in tennis.

In the 1990s, Gibson faced serious financial and health issues. A 1996 public appeal led by her former doubles partner, Angela Buxton, raised nearly $1 million to assist her, reflecting the enduring respect and admiration for her legacy (City Colleges of Chicago Athletics, 2025).

Althea Gibson’s enduring legacy in the elite, racially exclusive domain of country club sports—namely tennis and golf—has been well documented in both public discourse and academic scholarship. Her career in golf is frequently interpreted as a continuation of the trailblazing path she forged in tennis, symbolizing the persistent challenges and triumphs of African American athletes in predominantly white sporting arenas. Scholars such as Earl Smith and Angela Hattery (2020), as well as Earl Smith and Marissa Kiss (2021), have underscored how Gibson’s athletic experiences within country club sports expose the deep-seated structural racism confronting Black athletes, particularly women, within the historically segregated and elitist spaces of golf and tennis. [2]

Gibson’s contributions to sport and society have been commemorated through numerous honors, including her induction into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1971 and the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1980. In addition, her legacy is sustained through public memorials, such as statues, as well as scholarships and athletic programs established in her name—initiatives that continue to inspire and empower future generations of athletes. [3]

Gibson died on September 28, 2003, in East Orange, New Jersey, from complications related to respiratory and bladder infections. She is buried at Rosedale Cemetery in Orange, New Jersey, in the Juniper Section, Row 2, Grave 7. [4] [5]

___________________Reference Notes_____________________

[1]. The American Tennis Association (ATA) was established because of rigid social segregation on Thanksgiving Day, November 30, 1916. Representatives from over a dozen African American tennis clubs convened in Washington, D.C. The ATA hosted its first National Championships in August 1917 at Druid Hill Park in Baltimore, Maryland. The tournament featured three events: men’s singles, women’s singles, and men’s doubles. https://www.yourata.org/history

[2]. I wonder ALOUD: where are the “coattails” that flow from the pioneering Black athletes who participated–and at times dominated–in horse racing; bicycling; golf & tennis? Answer: there are no coattails!

[3]. Douglas, D. (2014). Gibson, Althea (1927-2003), tennis player and professional golfer. American National Biography

[4]. Find a Grave. (n.d.). Althea Neale Gibson. Retrieved May 22, 2025, from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7903760/althea-gibson

[5]. In a strikingly dismissive and poorly informed obituary, New York Times writer Robert McG. Thomas, Jr. opened with the following line: “Althea Gibson, the gangly Harlem street urchin who parlayed an asphalt championship in paddle tennis into an unlikely reign as queen of the lawns of Wimbledon and Forest Hills, died Sunday. She was 76.” This characterization, laced with condescension, not only diminishes Gibson’s profound athletic accomplishments but also reflects a troubling tendency to frame Black excellence through the lens of caricature and surprise.

_____________References (APA 7th Edition)_______________

Biography.com Editors. (n.d.). Althea Gibson. Biography. https://www.biography.com/athletes/althea-gibson

Brown, A. (2021). “Uncomplimentary Things”: Tennis player Althea Gibson, sexism, homophobia, and anti-queerness in the Black media. The Journal of African American History, 106(2), 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1086/713677

City Colleges of Chicago Athletics. (2025, February 5). Profile in Black sports history: Althea Gibson. https://citycollegesofchicagoathletics.com/news/2025/2/5/general-profile-in-black-sports-history-althea-gibson.aspx

Douglas, D. (2014). Gibson, Althea (1927-2003), tennis player and professional golfer. American National Biography, https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1901008

Gibson, A. (1958). I Always Wanted to Be Somebody, ed. Ed Fitzgerald. New Chapter Press.

International Tennis Hall of Fame. (n.d.). Althea Gibson. https://www.tennisfame.com/hall-of-famers/inductees/althea-gibson

National Museum of African American History & Culture (n.d.). Leveling the Playing Field: Althea Gibson. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/leveling-playing-field-althea-gibson

National Women’s History Museum. (n.d.). Althea Gibson. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/althea-gibson

PBS. (n.d.). Althea Gibson biographical timeline. American Masters. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/althea-althea-gibson-timeline/5393/

Smith, E. and Kiss, M. (2021, April 1). Why are there so few Black American players in MLB 74 years

after Jackie Robinson took the field? The Philadelphia Inquirer. Available at: https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/baseball-black-african-american-players-jackie-robinson-

20210401.html

Smith, E., & Hattery, A. J. (2020). Bad boy for life: Hip-hop music, race, and sports. Sociology of Sport Journal, 37(3), 174–182.

Smith, E. (2000). There was no golden age of sport for African American athletes. Society, 37(3), 45–48.

Thomas, R. McG., Jr. (2003). Althea Gibson, First Black Wimbledon Champion, Dies at 76. New York Times,

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/28/obituaries/althea-gibson-first-black-wimbledon-champion-dies-at-76.html?searchResultPosition=22

Yven, D., & Dyer, E. (2021). The legacies of tennis champions Althea Gibson, Arthur Ashe, and the Williams sisters show the persistence of America’s race obstacles. Race and Social Problems, 13(3), 195–204.